They say everyone has a book in them – but adopted Islander and lifelong seafarer Tony Mansbridge could write a whole shelf full of them.

They say everyone has a book in them – but adopted Islander and lifelong seafarer Tony Mansbridge could write a whole shelf full of them.

In fact the energetic 75 year old is in the process of writing his memoirs – not to mention still putting in six or seven hours a day at his workshop, where he’s building a 26-ft clinker launch in mahogany.

“There’s a lot of physical work, heaving lumps of timber around and jumping in and out of the boat” says the irrepressible Tony, “but it keeps you fit, and I wouldn’t miss it for the world.

“I look at some retired people who just waddle around and don’t seem to do very much – well, that’s certainly not the life for me!”

Adolf’s part in it

However, had it not been for Hitler and his bombs, Tony might never have come to enjoy an exciting life on the high seas.

The family lived in Wembley during the war, an area that was heavily bombed because of its proximity to an ammunition site.

The family lived in Wembley during the war, an area that was heavily bombed because of its proximity to an ammunition site.

His dad Don had been working as an ambulance driver, which gave him access to petrol for rare excursions.

“We had a big open-top Worsley, dad’s pride and joy” recalls Tony, “and our excursions gave us some breathing space from the constant bombing”.

After one particularly severe bombing that demolished an adjoining house, Don decided the family needed a real break and took only child Tony and his mum by train to visit relatives on the Isle of Wight.

The stay remains vivid in Tony’s memory not just for the secure feeling of being on the Island – but also because V.E. Day came while they were there, and they found themselves caught up in all the exuberant end-of-war celebrations on Ryde seafront.

“People were ecstatic with joy and relief, laughing and crying” he recalls. “It was one of the magical moments of my life”.

They returned to Great Preston Road in London only to find it so badly bombed that Tony’s dad instantly called in a removal firm and shipped the family back to the Island lock, stock and barrel.

Don had no work and the family survived in a grim little flat with a tin bath in the kitchen – not much better than what they’d left behind in London, but at least they felt safe.

Gradually Don found work, ultimately as a furniture salesman travelling on the mainland, which enabled the family to move to St Helens.

High hopes

Tony’s parents naturally wanted the best for their only child after such a traumatic early start, so Tony was duly packed off to private school.

But he was always pretty clear that the world of academia held no appeal for him.

“I was not a willing pupil – GCEs meant nothing to me” he says.

“I knew what I was born for, and school did not come into this plan!”

“My parents and teachers expected me to become a solicitor or something –a thought that horrified me”.

Happily, Tony was very clear on what he did want to do. He was always fascinated by the boatyard near his home, and instinctively knew that boats were “it” for him.

Which was why he joined the Merchant Navy as a raw 16 year-old recruit – and began working with a human ‘cargo’ – people who wanted to flee the rubble of their old homes in Britain and make new lives in Australia.

It was certainly a dramatic way to begin his career as a seaman: there were 1,000 emigrants aboard the Shore Savel Line that left Southampton’s Town Quay, and the ship was barely equipped for human cargo, with no air conditioning or other basic facilities.

It proved to be a hair-raising voyage, hitting bad weather – including a four-day hurricane that Tony says saw the ship being ‘methodically torn apart’, and a terrifying fire breakout in the ship’s hospital halfway across the Indian Ocean.

“I was steering the ship some days and it was like a giant roller coaster” he says. “The view from the bridge I will never forget – the waves coming up behind us were as huge as mountains”.

Miraculously, the emigrants were finally safely delivered to Sydney, Australia – and Tony went on to do another trip on the same ship. “Glutton for punishment or what?” he laughs.

His own Suez Crisis!

He also recounts his time on the ESSO London tanker – what he describes as another disaster zone.

“I seemed to get all the ropey ships as this one was in danger of falling apart!”

Still aged only 18, he was faced with dodgy boilers that were in danger of blowing as it set sail for the Persian Gulf via Suez.

Then the ship found itself as ‘piggy in the middle’ between British and Russian Naval forces and had a close encounter with a low-flying jet.

The biggest drama was when the ship hit fog in the Suez Canal and the Egyptian pilot managed to swerve the vessel into a bank, knocking off its rudder and propeller and leaving it stranded there, blocking the entire canal to any other traffic.

The ship was towed by the ocean-going Dutch tug, Wheitsy and a smaller London-style tug which broke down during the operation, leaving engineers to do repairs during a full gale.

Finally the ESSO reached the port of Bari in Southern Italy where it was dismantled – literally with the crew still on board!

When Tony and the rest of the crew did leave the ship for return to London, it was by air, in a Dacotta. It took off from a field, narrowly missing a hedge and landed at Southend Airport in thick snow, slithering to an abrupt halt.

“A coach took us to ESSO House in London where we were paid off in wads of £1 notes… I felt rich!” he says.

For Tony, it was then onto a mail train to Portsmouth and back to his beloved Isle of Wight.

Homeward bound

Still aged only 20, but with a wealth of marine experience, he landed a job at Woodnuts Boatyard on the Duver at St Helens – which lasted for six months until the firm went bust.

He managed to get work at Bembridge Sailing Club, but only so that he could save enough money to buy his own workshop building at a Government Surplus Auction being held at Culver Downs.

He bagged the 60ft x 20ft workshop for the princely sum of £65 – assisted by old school friend Guy Chappel who put down half the cash. Their plan was to start a boat building and repair business, but with nowhere to put the workshop they stored the parts at the Keith Nelson Boat building site at Bembridge Harbour.

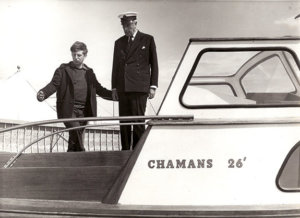

“It took months to sort out but eventually we got the go-ahead and with the help of my dad we erected our workshop and called the business Chamans, which was a combination of our two surnames.

Chamans years

The Chamans business became known for its wooden clinker boats, and one of the first commissions was from Maurice Oakham, who ran the Ryde Canoe Lake franchise and deckchairs at The Pavilion.

“We didn’t take him seriously at first but on his third visit he showed us half of a model boat and asked us to build a 36-ft version to carry 40 passengers.

“He didn’t have a drawing for us to work from so we built Telstar by scaling all measurements off this small model.

“Unbelievably the boat got finished and the last I heard a few years ago, it was still afloat”.

Tony and Guy followed Telstar with a fishing boat and then a 26-ft cabin cruiser that was built on spec.

They took that one to the Island Industries Fair at Ryde Airport –and were delighted when the late Lord Louis Mountbatten came aboard and greatly admired the craft. Sadly, it was not long afterwards that the Earl died at the hands of IRA terrorist bombers.

After an exciting and challenging seven years running the business, Tony went to work for Cheverton Workboats, where all his experience was brought into play.

“I ended up working all over the place,” he says.

From delivering boats all over Europe to being involved with big events such as the Paris Boat Show, Tony’s passion for boat building took him on journeys that few other careers could have offered.

He has a fund of colourful tales – like the time he was sent to bring back a damaged craft from the storm-hit 1979 Fastnet Race.

He set sail on the ferry from Ireland to Pembroke with the damaged craft on a trailer, and hit another gale, which led to the yacht smashing into the side of a lorry and sustaining even more damage.

By the time he finally delivered what was left of it back to Hamble Marina for towing across the Solent, the journey had involved detours along a railway track and swaying precariously across the Severn Bridge, which had been closed to all other traffic because of the high winds.

“It was a great relief to say ‘job done’ on that one – but it was only just!” he laughs.

With his enthusiasm for boats still as high as ever, Tony continues to enjoy his daily routine in the workshop, working usually from 9am until 3.30pm, a workload that would defeat many a younger person.

“It’s not hard work when you’re doing what you love to do” he says.

And as for those memoirs? Father-of-two Tony says they are being written mainly for the benefit of his family, so that upcoming generations will be able to reflect on a life lived to the full.