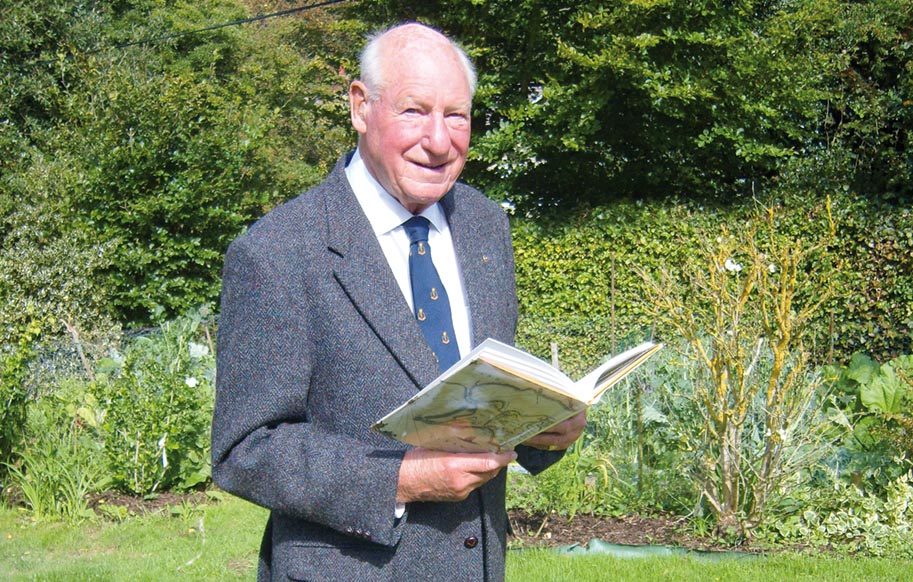

To hundreds of his patients he was simply known as Dr. Hooper, a general practitioner who worked for more than 30 years at the practice in Pyle Street, Newport. But in an active and very varied lifestyle, there has been much more to Dr. Paul Hooper than just diagnosing ailments and writing prescriptions. Now 85, Dr Paul – as he likes to be known – has taken time out to look back on a remarkable career that has embraced the Korean War, pioneering work in children’s medicine, writing a book, and receiving the ultimate accolade from his fellow doctors.

To hundreds of his patients he was simply known as Dr. Hooper, a general practitioner who worked for more than 30 years at the practice in Pyle Street, Newport. But in an active and very varied lifestyle, there has been much more to Dr. Paul Hooper than just diagnosing ailments and writing prescriptions. Now 85, Dr Paul – as he likes to be known – has taken time out to look back on a remarkable career that has embraced the Korean War, pioneering work in children’s medicine, writing a book, and receiving the ultimate accolade from his fellow doctors.

Dr. Paul lives in a tranquil retreat in Chale Green with his wife Elizabeth, a far cry from the hustle and bustle of the Midlands where he was brought up, or of the Far East where he served during the bitter conflicts of the early 1950s.

Born in Birmingham in 1926 – the year of the general strike and the year Oxford sank in the Boat Race – Dr Paul went to boarding school at the age of nine in Derbyshire, and then returned to the Birmingham area, attending a school near the Austin car factory at Longbridge. But in 1939, at the start of the Second World War, the location was considered too close to a potential bombing target, so he and his classmates were evacuated to North Herefordshire.

He later attended Bradfield College, Berkshire, and in 1942 decided he wanted to pursue a career as a doctor. So he attended Birmingham University with the added advantage of being able to live at home with his parents. After qualifying as a 23-year-old, Dr Paul worked in the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham for a year before being called up for National Service in 1950.

“I was asked where I would like to be posted and I said my first choice was Europe, and my second choice was the Middle East – so I was sent to the Far East,” he smiled. “I arrived in Hong Kong on a troop ship the day before Christmas, and virtually everyone had disappeared, so I spent Christmas Day in the Mess with two Scotsman – not the best Christmas I have ever had.

“Shortly afterwards I was posted as Regimental Medical Officer to the 1st Battalion of the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry in the Hong Kong new territories. We were then despatched to Korea, and within a week of arrival were engaged in battle, and I didn’t really have a clue what was going on.”

After the initial conflicts died down, the then Lieutenant Paul Hooper was promoted to Captain, and he and the Battalion moved to an area close to the River Imjin. That was where he witnessed some of the worst of the fighting and injuries. He treated over 300 battle casualties in his aid post, many with horrendous wounds.

After the initial conflicts died down, the then Lieutenant Paul Hooper was promoted to Captain, and he and the Battalion moved to an area close to the River Imjin. That was where he witnessed some of the worst of the fighting and injuries. He treated over 300 battle casualties in his aid post, many with horrendous wounds.

“All apart from two casualties survived, but that wasn’t down to me it was down to the excellence of the Indian Field Ambulance who supported us,” he said modestly. “The medical team comprised me, a sergeant, corporal, bat man and driver, and our ambulance was a ramshackle affair, in as much it was a jeep adapted to hold a couple of stretchers at the back – very uncomfortable, bumpy and a cold ride for the casualties.

“So I invented a makeshift ambulance, using a bren (light machine) gun carrier which was extended to carry a stretcher on each side with an engine in the middle. The advantages were it was bullet proof, warmer because of the engine, and more comfortable. All the battalions in the division were later equipped with these bren gun ambulances, but I was never credited with inventing it.”

After being posted to a hospital in Japan, Dr. Paul returned to England in 1952 – but to this day still keeps in touch with some of the soldiers he worked alongside in the Far East. During his time in Korea he kept a detailed diary of events, a copy of which is now in the Regimental Museum in Shrewsbury.

His intention upon his return home was to become a surgeon, but although he continued working in Birmingham’s QE Hospital, he failed the second part of a compulsory exam, so headed instead into general practice.

That brought him to the Isle of Wight, after he answered an advert in British Medical Journal, and he worked initially in Ryde for a year before settling here permanently, joining the practice in Pyle Street, Newport in 1959, and staying until January, 1991.

That brought him to the Isle of Wight, after he answered an advert in British Medical Journal, and he worked initially in Ryde for a year before settling here permanently, joining the practice in Pyle Street, Newport in 1959, and staying until January, 1991.

“I spent more than 30 very happy years there, and would not have missed a day of it,” said Dr. Paul. “I was also on the surgical staff at St Mary’s Hospital working under a very fine surgeon Gordon Walker, who improved the surgical services on the Island very much. I did a lot of emergency surgery when standing in for one of the juniors, who had to have time off. So in the end I did get to do some surgery, which gave me the best of both worlds.”

While working in Pyle Street, Dr. Paul became one of the first people in the country to work on what was known as developmental paediatrics. He explained: “Rather than just looking after children when they were poorly, we monitored their progress from birth to school entry age to make sure they didn’t have any difficulties that might upset their education, such as deafness, vision or behavioural problems. The aim was to do something about it before they went to school, so they would not be disadvantaged.”

A grant from the Ministry of Health allowed Dr Paul and other doctors around the country to carry out a survey and write a report on their findings, but to his dismay the report was left on a Ministry shelf to gather dust, and he is bitterly disappointed to hear that his former practice has now also abandoned the scheme.

Just before his retirement Dr. Paul enjoyed one of his proudest moments when he was invited to become the Provost of the Royal College of General Practitioners for the whole of the south of England, stretching from Portsmouth to Basingstoke, Newbury, Bath and Poole, and also including the Channel Islands.

“I regard that as a great honour because you are elected by your colleagues. I was Provost for the two-year term, and the area embraced between 4,000 and 5,000 doctors,” he explained.

After retirement Dr. Paul was able to pursue other interests. A keen member of the Isle of Wight Historical Association and former chairman, he researched and published a book ‘Our Island in War and Commonwealth’ highlighting the part played here between 1640 and 1660 during the Civil War. Although Carisbrooke Castle is always associated with the Civil War, and Charles I’s imprisonment in particular, Yarmouth and Sandown Castles were also used to hold prisoners during the conflicts as well as an area near Brook.

“It had long been a wish to write a book on what happened on the Island during the Civil War and just afterwards, until King Charles II came to power. It took me about eight years to do, and was published in 1999. I am told that the first cannon shot in the Civil War was fired from Cowes Castle at a ship that was carrying supplies from the Island across to Portsmouth for the Royalists,” said Dr. Paul. “I found it surprising just how many people were sent down here as prisoners apart from King Charles.”

“It had long been a wish to write a book on what happened on the Island during the Civil War and just afterwards, until King Charles II came to power. It took me about eight years to do, and was published in 1999. I am told that the first cannon shot in the Civil War was fired from Cowes Castle at a ship that was carrying supplies from the Island across to Portsmouth for the Royalists,” said Dr. Paul. “I found it surprising just how many people were sent down here as prisoners apart from King Charles.”

Dr. Paul’s other positions have been numerous – former chairman and Medical Officer for the Marriage Guidance Council, regular MO at the County Show, former chairman of Chale Parish Council and for many years was on the executive committee of the Campaign for the Protection of Rural England (CPRE). He later became president of the Island branch of the CPRE; is still president of the IW Historical Association, and a member of Newport Rotary Club.

Despite all his duties Dr. Paul still finds time to tend the garden and enjoys reading, but is not particularly a fan of television. He added: “I have enjoyed my life so much, and am still doing so. I wouldn’t have changed a moment of it. After all those years practicing in Pyle Street, it is difficult to walk through Newport without someone saying ‘hello Dr, how are you?’ which is wonderful. Only recently someone came up to me in the street. I didn’t recognise him but he said ‘you saved my life’, which I find very gratifying.”