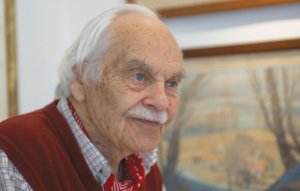

Cavendish Morton truly is a Renaissance Man. Well known on the Island for his maritime and landscape paintings, this artist whose life has spanned almost a century has worked as a boat builder, book illustrator, teacher and designer of sports cars. And his paintings reflect a versatility which is rare today.

Cavendish Morton truly is a Renaissance Man. Well known on the Island for his maritime and landscape paintings, this artist whose life has spanned almost a century has worked as a boat builder, book illustrator, teacher and designer of sports cars. And his paintings reflect a versatility which is rare today.

You are struck by how modern the paintings seem. They are structural and clean lined while a wealth of detail both softens and adds to the information. His boats are anatomically perfect, while the water has a lovely translucence and the weather drives down in angry slashes.

“I haven’t looked at this one for 60 years,” says Morton, closely examining the curtain of sea behind the yacht. “I thought I’d buggered it up with those lines. But it actually shows the movement!”

A prolific artist, he has painted subjects which are almost accidentally commercial: accidental because the subjects which appeal to him chime with today’s photographic love of detail. His ability to portray intricacy was no accident. He and his twin brother Concord were educated at home in Bembridge by his father, a theatre portrait photographer, and his mother, a writer of popular novels writing under the name of Concordia Merrel. In 1926, at the age of 15, during the summer of the General Strike, Cavendish and Concord were sent off to St Ives in Cornwall to learn to build boats. “Our parents’ idea was that we saw and felt the structure and it would help with our painting or if we were doing sculpture,” said Morton. “It wouldn’t have been allowed today,” he smiles. “I had no insurance or anything like that!”

They built a 41ft fishing boat. It was, says Morton, “a marvellous thing to do. We used our hands, there were no power tools of course.”

Three years later, at 18, after a stint painting at Nicholson’s boat yard in Gosport, Morton had a painting exhibited in the Royal Academy in 1930. “It was the Shamrock V, a J class. A boat built for Sir Thomas Lipton for Americas Cup. I realise then how valuable it had been for me to work on the actual structure of a boat. Shamrock V was on metal frames with wood planking.”

Three years later, at 18, after a stint painting at Nicholson’s boat yard in Gosport, Morton had a painting exhibited in the Royal Academy in 1930. “It was the Shamrock V, a J class. A boat built for Sir Thomas Lipton for Americas Cup. I realise then how valuable it had been for me to work on the actual structure of a boat. Shamrock V was on metal frames with wood planking.”

His art was fed by a growing passion for sailing, and he escaped to Cowes whenever he could. “I sailed in Velsheda, a J class, among others. I was inspired by the wonderful effects of rope and sail on the sea, and by the various weather conditions – a slight breeze with spinnakers blowing out, to sailing in heavy weather. I was dismasted in the North Sea. It’s always interesting when the mast goes!”

But Morton was hardly a dilettante artist. He became interested in aircraft, and started working in advertising for air manufacturers Saunders Roe in East Cowes. He and his brother were finding it hard going selling portraits, so “we supplemented our ordinary paintings by producing aircraft manuals and aircraft advertising, flight covers and so on.”

He also found work in the steel industry in Glasgow, producing nearly 20 drawings for Beardmore steel works, and did similar work for shipbuilders John Brown. “That sort of kept enough income to live on,” recalls Morton.

Word of their skills got round, particularly in the aircraft industry, but just as work in freelance industrial painting really started to take off the war came. Morton was posted to Saunders Roe and joined the Home Guard, and his experience belies that portrayed in television’s Dad’s Army. “We only paraded once a week but sometimes one was in uniform and there was no time to change before getting back to the office. We took it very seriously.” As a result he had little time for painting.

But as soon as he could after the war he picked up his paintbrushes again. And immediately got a picture into the Royal Academy. “I thought I was jolly lucky to get a picture in straight after the war,” he says with typical modesty.

His marriage to Rosemary Britten, he says, was “a good move, because my great passion was for classical music.” They had met as young people growing up in Bembridge, and it had been music that had drawn them together. As well as being a pianist, she played cello and flute. During the war she served in the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF) as an Intelligence Officer, and, Morton confides, had been one of the few women to be shot down during the war:

“She was in a Halifax bomber, towing gliders on an operation. They’d dropped a glider and got hit by Anti-Aircraft fire and had to make a forced landing on a US airbase on one side of the Rhine with the Germans on the other. Of course as an Intelligence Officer she shouldn’t have been there, and she kept it secret for 40 years.” He is obviously still proud of her pluckiness. “There is plenty of gallantry on her side of the family,” he says.

After they married they moved to Suffolk, eventually settling in Eye (with a holiday cottage in Aldeburgh), where he exhibited to local galleries and she taught music. He became a member of the committee of the Aldeburgh music festival, with Benjamin Britton and Peter Piers. “It was fantastic to see some of the great musicians at work!” he enthuses. And here two of his great passions coincide, for he began a series of paintings documenting the conversion into a concert hall of the collection of old barns set amongst reed beds which comprise Snape Maltings.

After they married they moved to Suffolk, eventually settling in Eye (with a holiday cottage in Aldeburgh), where he exhibited to local galleries and she taught music. He became a member of the committee of the Aldeburgh music festival, with Benjamin Britton and Peter Piers. “It was fantastic to see some of the great musicians at work!” he enthuses. And here two of his great passions coincide, for he began a series of paintings documenting the conversion into a concert hall of the collection of old barns set amongst reed beds which comprise Snape Maltings.

Disaster befell the venue just two years after its opening. On the first night of the festival, the Maltings were completely gutted by fire, which ironically gave Morton the subject matter for some of his favourite paintings. “I experimented to get the effects of the steel after the fire, using a technique of printing onto bits of paper to build the effect of blistered steel. I splattered it and messed about with the surface – it was interesting and gave a texture in the steel which plain watercolour could not have achieved.”

A painting of Britten’s charred-edged score of Idomeneo, found behind the stage, again documents the poignancy of seeing the destruction of the building which he was instrumental in supporting. Amazingly though, restoration took just one year and the festival, which had partly relocated to nearby Blythburgh after the fire, was back in the beautiful location which has since become a fixture in the classical music calendar.

For the rest of the time he was painting Suffolk landscapes, and as he so tellingly says, “apart from other things I did”, he was an early chairman of the Gainsborough House Society, a charity which runs the house in Sudbury where Thomas Gainsborough was born. He introduced more modern works from Suffolk and Norfolk, such as an early exhibition of works by Lowry.

“I’ve never been short of work, I’ve been constantly busy. I’m much too interested in people and teaching and seeing works by amazing, brilliant artists,” he says. In true Renaissance fashion he became a technical artist involved with Snetterton motor racing, designing the bodies of cars, some of which raced at Le Mans. He has also illustrated two books for Dorothy Hammond Innes (whose author husband was a one-time sailing companion of his), and a book on the Bembridge Redwings by David Swinstead.

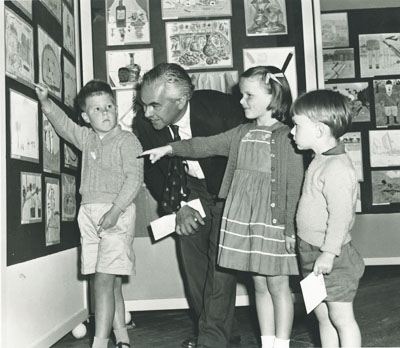

Unsurprisingly, given his precocious attitude to change, he did some work in television, running art competitions for children. “We didn’t give prizes or false money!” he grins wickedly, referring to the scandals recently uncovered on today’s programmes.

Of today’s art, he describes himself as “a little bit critical of – what’s the word they use now? Conceptual artists.” He doesn’t have a lot to say on Damien Hurst, and of “that nice chap Gormley” admires the sheer logistics of his recent installation, where people went into a room filled with fog. “He managed to get a fog into a room without poisoning people! So you opened a door and you found yourself isolated. I don’t object to things like that, it’s interesting.”

“I’m not over-critical of the modern movement, because some have proved wonderful in freeing art up. But I still find French impressionism probably one of the greatest things that happened to art. It released artists from the studio.”

But it was teaching which he found to be one of the most rewarding things. He taught art for 10 years in a girl’s school, as well as in further education. “A lot of people were extremely determined to paint, and it was wonderful to encourage them.”

Sadly his wife Rosemary developed multiple sclerosis, and the couple returned to Bembridge, where Morton nursed her until her death five years ago. “If she was still alive this year would have been our diamond wedding plus two,” he says. He continued to paint while nursing her, tending towards watercolour to avoid the smells associated with other media. He became chairman of the Isle of Wight Art Club, doing demonstrations for them when he could – “bearing in mind I was nursing Rosemary. It was terrible in the end, she was completely blind…”

He didn’t find solace in painting, but in the music which was so associated with Rosemary. Sadly after a year his own sight started to go and he is now partially sighted. But he reflects philosophically on his life as an artist:

“When you are going blind you look back on your work and you realise that’s all finished. Your life has ended. That’s a shock. Then, you look back again and think, ‘I may have done something.’ And I know that some of my work has given a tremendous amount of pleasure to others. But that,” says this generous and unassuming man, “sounds like boasting.”

There will be an exhibition of Cavendish Morton’s paintings at Castle house, Lower Green Road, St Helens PO33 1XY. The exhibition runs from 22nd – 26th March. Tel: 01983 872768. Or visit www.gibsonmoore.com.