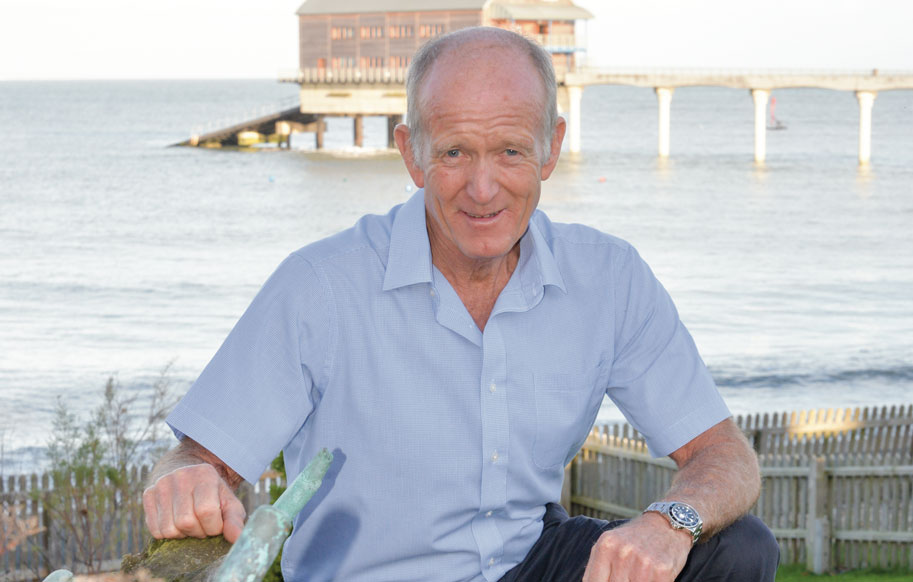

Part two of the feature on the exploits of deep sea and shipwreck diver Martin Woodward.

Part two of the feature on the exploits of deep sea and shipwreck diver Martin Woodward.

Although Martin Woodward has found gold and other treasures deep down on the seabed around the Isle of Wight, he has never once sold any of it for his own gain.

Instead Martin has kept his unique collection of artefacts to share with the public, displaying them at his ‘Shipwreck Centre’ maritime museum at Arreton Old Barns. There is something of interest for everyone at the Centre, from Spanish gold and silver to antique and present day diving equipment, ship’s bells and portholes, and a multitude of other intriguing relics from the past.

Yet Martin is quick to point out that wreck diving around the Island has merely been a hobby, saying: “My job was deep sea diving, with wreck diving a side activity that I have always loved.”

He explained: “I did a lot of deep sea diving in the North Sea, mainly off Aberdeen, which was very well paid. We worked for one month and then had one month off. So I could work up there for a month, and then come back down here and continue my hobby of ‘playing’ off the wrecks.”

His deep sea diving work was specialist, and sometimes extremely dangerous. He reflected: “I lost a lot of friends in the early 1970s, but I am not one to dramatise, because you can lose friends in everyday events. Working in the North Sea I did everything; cutting, burning, laying sandbags over pipelines – I was a multi-tasker, but you had to be in those days. My speciality was photography so I did all the underwater inspection photographs and videos, but I still did everything else because you had to.”

He spent six years diving in the North Sea often going down to around 600ft. He said: “It was a bit like a space station, but with a complex of chambers built into the bottom of the ship. You went into the compression chambers and pressured up to whatever depth you are working at, and then you lived at that depth for a month, normally working eight-hour shifts. You worked outside the bell in hot water suits which were fine when they worked, but often they didn’t! I think the longest shift I had down there was over 17 hours. Then at the end of the month you did five days of decompression before you returned to normal life. But it was like any other job to me.”

He spent six years diving in the North Sea often going down to around 600ft. He said: “It was a bit like a space station, but with a complex of chambers built into the bottom of the ship. You went into the compression chambers and pressured up to whatever depth you are working at, and then you lived at that depth for a month, normally working eight-hour shifts. You worked outside the bell in hot water suits which were fine when they worked, but often they didn’t! I think the longest shift I had down there was over 17 hours. Then at the end of the month you did five days of decompression before you returned to normal life. But it was like any other job to me.”

He continued: “I had a few scary moments in bad conditions. One day the diving bell got caught up in a wire in rough conditions, and when the ship we were diving off blew off station it left us at an horrendous angle. Fortunately the wire which had gone round the tube that supplied our gas, broke out, and we were ok. Yes it was dangerous sometimes, but I would rather do that than drive a taxi!”

Martin admits that in the early days of deep sea diving there was no such thing as health and safety regulations – it was just a case of getting the jobs done. One of those jobs was actually diving down the inside of huge legs of oil rigs.

He said: “We went down inside the legs of the rig, maybe 200ft, to recover drill bits or do other work. Some divers didn’t like doing it, but I did it because I would be getting ‘back-handers’ all the time. The basic rig leg was 3ft across which was luxury; I used to do a lot of 30-inch ones, which you could just about get down.

“I was down below the mud line sometimes, but you weren’t going to come to much harm. It was good fun, but some of the work we did would never be allowed now. These days you have to have four people on site to go two feet under water – ridiculous! Health and Safety killed the small diving business.”

He recalls: “When I was working in the Gulf we had a rig blow out, and it all disintegrated. It left a bubble of gas burning, and we were surveying down to 200ft, just diving with air tanks. It was dangerous, but fun. I wouldn’t have missed a moment of it.”

Although his days working on and below oil rigs have long gone, Martin still enjoys the thrill of wreck diving. As well as the 2,000 or so wrecks recorded around the Isle of Wight there are an incredible 250,000 under the water around the British Isles

He has dived on some 600 around the Island, but reckons: “There are still plenty out there to be found. The biggest one I looked for was the HMS Victory – the one before the Victory you can see in Portsmouth Dockyard. In the end it was found purely by accident a few years ago. It was built in 1737 and was the finest ship in the world at the time. I would loved to have found it, but that was one that got away. It was wrecked off the Channel Islands in 1744, north of Alderney, and was eventually found by an American company.

“There are a few I would still like to find, but they are not easy because they are way out in the English Channel. It is a question of perseverance because the records might be wrong and wrecks could be 10 or 12 miles away from where they are supposed to be. I do it for fun, and because I like doing it; putting stuff in the museum so people can enjoy it. If artefacts were still tucked way on the sea bed under five feet of sand no one would ever see them.”

“There are a few I would still like to find, but they are not easy because they are way out in the English Channel. It is a question of perseverance because the records might be wrong and wrecks could be 10 or 12 miles away from where they are supposed to be. I do it for fun, and because I like doing it; putting stuff in the museum so people can enjoy it. If artefacts were still tucked way on the sea bed under five feet of sand no one would ever see them.”

Martin opened his first museum in 1978 in Bembridge, and was there for 28 years, before moving to Arreton Barns. He said: “My philosophy is that as long as I can pay wages and don’t make a loss, I just grin and bear it. As a one-man business with no funding it is a struggle.”

He added with a laugh: “But we are keeping our heads above water! Sometimes I wish I hadn’t bothered – but I don’t wish that for very long. It is gratifying that people come and see the things I have found, and appreciate I have been out there, found the stuff and put it in the museum. It’s local history and I feel I have a moral responsibility to keep the collection together.

“The easiest thing in the world would be to sell it, but I can’t do that. It would be dispersing a collection about the Isle of Wight area that is quite unique, and it should stay as a collection.

“Each item I have brings back a memory for me. I have found hundreds of portholes over the years, but I know where each one came from, because it means something to me. It is fascinating because it is like an underwater time capsule.”

Martin has dived all around the world, including off the United States, the Caribbean, Cape Verde Islands and Ecuador, his favourite area being the crystal clear waters around the Philippines.

He added: “If you don’t have to rely on earning a living from it, and keep persevering, you will find stuff out there. I still enjoy it and will be doing it until they drag me out of the water with rigor mortis. It has been an interesting life, and I hope there is still a lot more interest to come.”